ANALYTICS

04.01.20 17:15

Despite all attempts to falsify history in the Republic of Armenia, the truth cannot be hidden. Particularly recalling the past of the Azerbaijani city of Irevan, now completely destroyed with the completely expelled indigenous Azerbaijani population, on the site of which is the capital of Armenia Yerevan.

Arthur Hakobyan’s article “Yerevan in the 19th Century” published on the website vstokax.net (https://vstrokax.net/avtorskaya-kolonka/erevan-v-xix-veke/) despite the fact that the author did his best to write it “with of Armenian positions ”clearly indicates that Irevan (Yerevan) was an Azerbaijani city. We give it in full:

“No one would have thought that Yerevan (Erivan) of the 19th century could someday become the capital of the Armenian state. At the same time, despite the fact that the future Armenian capital was then still small, sometimes groomed and with terrible sewage, Yerevan already had features that were interesting compared to other cities.

In general, there was no division of labor in Yerevan. A trader and even an official could simultaneously have a garden and process it at his own expense. This is largely due to the abundance of the gardens themselves and good conditions.

According to Russian observers, Yerevan was the best place for gardening in the entire Russian Empire: any kind of fruit, regional or even foreign, could be grown here. The problem was that local gardeners were not particularly interested in this. By the way, from Yerevan were the best peaches and apples. In total there were 692 gardens.

The gardens here were also of considerable size, although the Armenians used vegetables most often at the table, and did not start lunch without them. The then Turks of Yerevan came up with the proverb: "The nightingale knows the dignity of roses and the dignity of greenery - Armenian".

It is funny that the traders also had a division of activity conditional, largely due to difficulties with local trade. A porcelain dealer traded carpets at the same time, while a pottery seller could carry seeds as well. Local Armenians gradually began to build full-fledged shops and not just bazaar shops. They went to Tiflis, Moscow, Warsaw, and Vienna for goods. These were the main points.

They studied with the city with difficulty, but the enthusiasm of the Armenians was more than the local Turks in the banal difference in the educational tradition. The Turks studied in cells in the courtyards of mosques, where there was no concept of discipline at all.

The only major institution was the Muslim Higher School, where 60 of the really aspiring students entered. At the same time, they did not pay mosques for education, but the mosque did.

Armenians studied in theological seminaries and church schools, which had their own libraries. The terrible bureaucracy annoyed everyone when they had to turn to Echmiadzin, the bishop of the diocese, the inspector of the seminary, and the trustees to solve the problems of one seminary.

Education in schools was carried out diligently, but because of the complex hierarchy, there were considerable problems.

Despite many problems, Yerevan was still able to become the main hub of the future First Republic. The vast and handicraft Alexandropol lost for one simple reason: while the manufactory was widely developed in it, capitalist relations had already developed in less developed Yerevan. Yerevan seized the initiative”. End of article.

Most interestingly, the author from the very beginning admits that “no one would have thought that Yerevan (Erivan) of the 19th century could someday become the capital of the Armenian state.” That is, it was an almost entirely Azerbaijani city with a small Armenian trade layer.

The author explains that the city has become the Armenian with “great enthusiasm” of Armenians in education. Alas, the Armenian nationalists really showed “enthusiasm” later on in the genocide and ethnic cleansing of the non-Armenian population. And, unfortunately, the Armenians instilled this “enthusiasm” in church colleges, schools, and seminaries, under the patronage of Echmiadzin.

They taught diligently. They taught to hate non-Armenians and listen to the "leaders." Spiritual and political. They taught extremism. What the Azerbaijanis did not teach in mosques and madrassas, where, as the author writes, “there was no discipline”.

And why is there strict discipline in mosques? Militants and terrorists there, unlike the schools of Echmiadzin, were not trained. And a person should pray not so much “because of discipline”, but as ordered by the soul.

But in schools, under the patronage of Echmiadzin, with their almost army discipline, young Armenians, apparently, were taught, first of all, not prayers at all. They were brainwashed with myths about the "Great Armenia" and the "exclusivity" of the Armenians. Future terrorists and fighters were prepared from them.

It was not by chance that in 1903 Tsar Nikolai the second ordered the confiscation of the property of the Armenian church and the removal of the schools from its subordination, but it was too late. The poisonous infection of nationalism has already been sown in the souls of many young Armenians. Which led to subsequent tragedies.

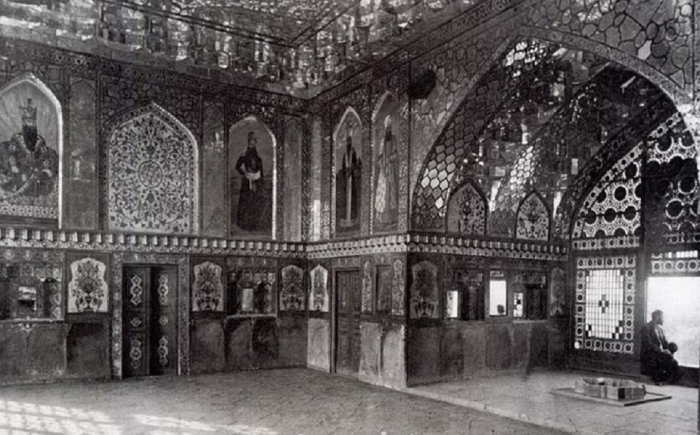

19th century Yerevan remained only in old photographs and in memories as the original and unique Azerbaijani cultural environment that disappeared (or rather, was barbarously destroyed). But the story is not over. It is impossible to build a durable state on lies and falsifications, on ethnic cleansing. The nationalist regime in Yerevan is not eternal.

KavkazPlus

Read: 307

Write comment

(In their comments, readers should avoid expressing religious, racial and national discrimination, not use offensive and derogatory expressions, as well as appeals that are contrary to the law)

News feed

-

MIA to identify individuals calling for blocking roads artificially during Rustaveli Avenue rallies

18:0024.04.24

-

Lazare Grigoriadis leaves prison

17:3024.04.24

-

Irakli Kobakhidze to participate in the Conservative Political Action Conference in Hungary

17:0024.04.24

-

16:1724.04.24

-

15:3024.04.24

-

Youth social entrepreneurship support project kicks off

14:5024.04.24

-

14:0024.04.24

-

Tbilisi Mayor deems new stadium construction as a mega project

13:2024.04.24

-

12:2424.04.24

-

Rustavi City Council Chairman dismissed

11:3024.04.24

-

10:2224.04.24

-

9:0024.04.24

-

Tusheti Protected Landscape in Georgia’s north-east to expand by 2,245 hectares

18:0023.04.24

-

17:2823.04.24

-

16:5623.04.24

-

16:2023.04.24

-

15:4423.04.24

-

15:0623.04.24

-

Georgian PM, UN representatives review cooperation

14:3523.04.24

-

14:0023.04.24

-

Four people were arrested for making and issuing fake driving licenses

13:2023.04.24

-

12:3923.04.24

-

Georgian, Croatian foreign ministers discuss “fruitful” cooperation

11:3023.04.24

-

Georgian foreign office welcomes border delimitation deal between Armenia, Azerbaijan

10:4523.04.24

-

10:0023.04.24

-

8:0023.04.24

-

18:0022.04.24

-

Prosecutor's Office arrests organized criminal group members involved in call centres

17:2722.04.24

-

Economy Minister: Georgian economy to become “one of fastest-growing” in Europe, wider region

16:5522.04.24

-

Deputy Economy Minister: over million travellers, “record-high” EU visitors entered Georgia in Q1

16:3122.04.24

-

Girchi Party sceptical about their Political Lobbying bill's support in Parliament

16:0022.04.24

-

Russian occupation forces illegally arrest two citizens of Georgia near village of Dirbi

15:3022.04.24

-

14:5722.04.24

-

Shalva Papuashvili: The age permitted for marriage - 18 years - will be written in the Constitution

14:1622.04.24

-

13:1022.04.24

-

Environmental Ministry tightens restrictions on Boxtree cutting

12:3422.04.24