09.11.23 16:50

Azerbaijan is currently offering Armenia a peace agreement within internationally recognised borders and with the unblocking of communications, in particular the Zangezur corridor. The conditions are very good. This is much more than what the Hayes in the South Caucasus generally deserve "according to historical justice". After all, the entire territory of the present-day Republic of Armenia is the historical territory of western Azerbaijan and south-eastern Georgia (Lore).

But this is not enough for the Khai nationalists. The most radical among them not only refuse to give up their revanchist claims to Azerbaijani Karabakh, but also claim the lands of other neighbours of their state, in particular Eastern Turkey and Southern Georgia (Samtskhe-Javakheti).

For those of the Khai nationalists who cannot restrain their appetites, it would be good to remember their own history of more than 100 years ago. When the Europeans offered them vast territories of the defeated Ottoman Empire, the nationalists wanted much more. What came out of it in the end was very well described by Albert Hakobyan (Urumov), a Khai historian from Turkmenistan, in his article "Armenia: How Russophobia was Hardened". Part 3 - Déjà vu of 100 years". ( https://eadaily.com/ru/news/2023/11/07/armeniya-kak-zakalyalas-rusofobiya-chast-3-dezhavyu-100-letney-vyderzhki ):

"In the autumn of 1918, the Central Powers were defeated. Interestingly, under the terms of the Mudros Armistice of 30 October, the Entente obliged the Ottoman Empire to withdraw from all territories outside its 1914 borders except... Batum and Kars. Until further notice. Yes, it can be said that the Anglo-French victory in the First World War saved Armenia. But perhaps we should not underestimate the will to live of the people themselves, who were able to establish semi-artisan production of shoes, woollen cloth, etc., and entrepreneurs who used all the proceeds from the sale to buy bread in the territories of southern Russia - the Don and Volunteer armies of the Whites. The German troops in Georgia, despite the fact that the White Movement did not recognise the Brest Peace, did not interfere with supplies.

A real famine occurred in December 1918, when Armenia, barely awake after the withdrawal of the Ottoman troops, attacked Georgian and German troops (Germany withdrew from the war a little later than Turkey) in the disputed Lori district as well as in Akhalkalaki. Georgia insisted on inter-state borders along the lines of former provinces. Why not counties? And how to determine which province belonged to whom? Armenia demanded borders that took into account the settlement of peoples. This would have led to a massacre that would have made 1915 look like flowers: the temptation to "tweak demography" for the sake of "fair borders" was too great. Well, both sides were engaged in this activity before and after the Armenian-Georgian war. Moreover, the "ethnic approach" would have completely cut off Armenia from Georgia by a strip of Azerbaijani territory: Azerbaijanis still predominate in Borchali, and Meskhetian Turks used to live in Akhaltsikhe. In any case, the means of diplomacy were far from exhausted, but Armenia preferred ultimatums and war.

The war lasted from 4 to 31 December with mixed results. On 17 January 1919, a peace treaty was signed with the mediation of the British, who had replaced the Germans: Borchali remained Georgian, South Lori Armenian and the Alaverdi mines (a quarter of the Russian Empire's copper) a neutral zone under British rule. For two months the railway through Georgia was blocked and no bread reached Armenia. This led to an unknown number of deaths: people, weakened by hunger, died of various diseases.

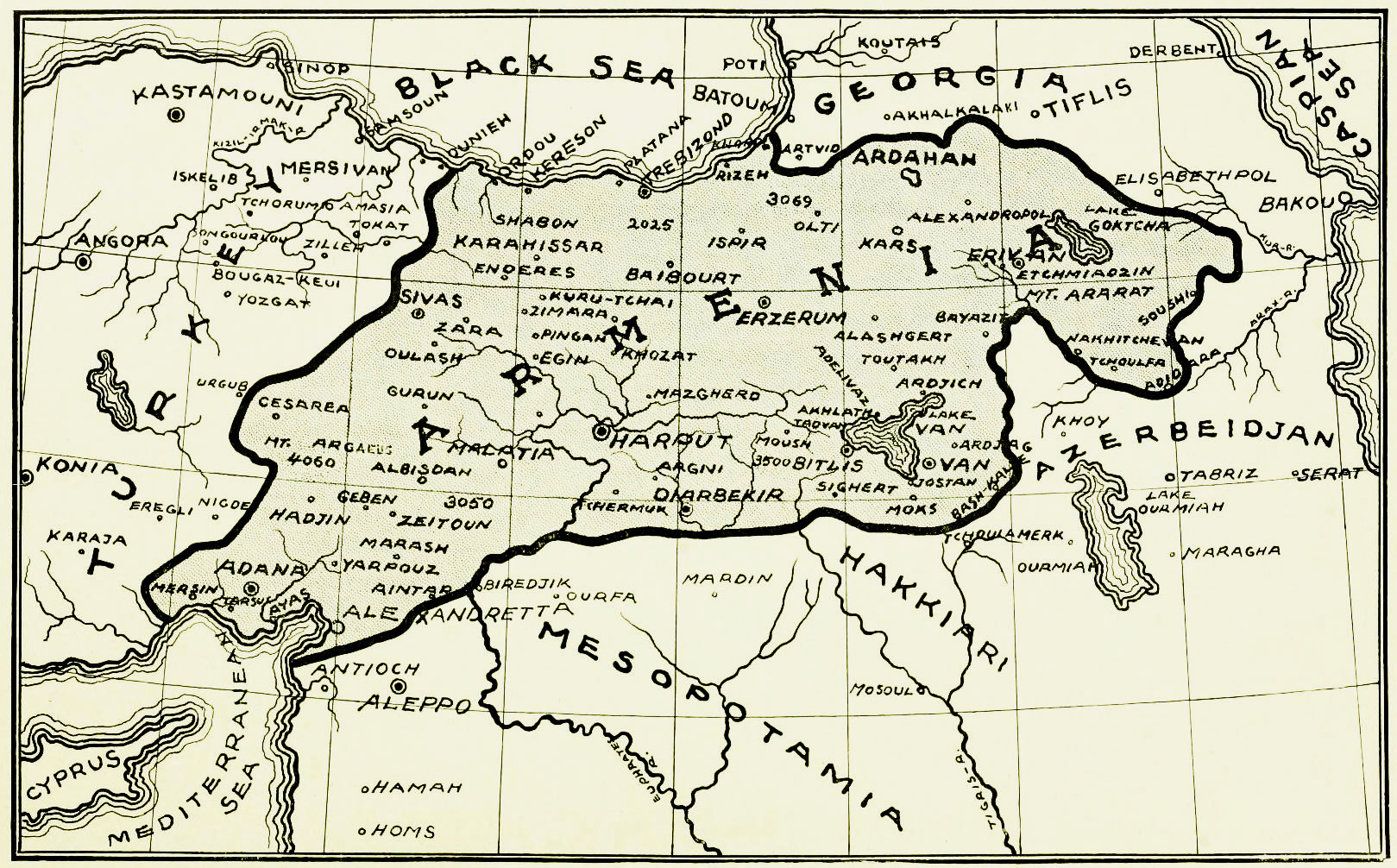

At the same time, the Entente gave permission for Armenia and Georgia to go to the borders of the Russian Empire in 1878. The town of Oltu (Olti, Oltisi; remember this name) went to Georgia. In fact, the area was controlled by detachments of pro-Turkish "partisans", but Tbilisi decided not to escalate the situation until the general situation around Turkey was clarified. The Armenians were more determined. Accompanying the map of 'six Armenian vilayets' (Fig.1), the author pointed out that the dying Ottoman Empire had agreed to cede three of them at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. Moreover, the Armenian-Turkish treaty, because of the special situation in Armenia, could be taken out of the framework of the general (future Sevres) treaty, i.e. concluded separately and ratified in mid-1919. Armenia rejected the "handout" and put forward its own demands on the borders at the conference:

The borders requested by Armenia at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919

Obviously, such demands raised the eyebrows not only of the Turks and other neighbours, but also of the Anglo-French. But you will laugh, the Sevres Peace Treaty of 1920, drawn up by the Paris and San Remo Conferences, practically satisfied the Armenian demands! Map of the partition of Turkey according to the Treaty of Sèvres:

The Armenians wanted not only a large part of the Armenian highlands, but also access to the Black Sea with the port of Trabzon, with borders based on the results of US President Woodrow Wilson's arbitration. The trick is that 'zones of influence' (read: occupation) have been created on Turkish territory: Italy (Antalya, Konya, Afyon), France (Adana, Sivas, Diyarbakir), Britain (North of Iraq) and the very important Straits Zone under "international control" mainly of London, Paris and Athens. Thus, in the "zones of influence", the establishment of self-governing bodies was allowed. But not of Turks! In the Italian part - Greeks, in the western part - Armenians, in the eastern part - French and in the British part - Kurds. The purpose is obvious: the dirty work of exterminating the Turks or forcing them into a "Bantustan" around Ankara was to be done by the Greeks, Armenians and Kurds.

Enough hypocrisy. Not only Turks and Kurds, but also Greeks and Armenians had rich experience in exterminating "peaceful enemy" populations (and why should it be any different?). The blood of tens of thousands of Turkish civilians in Kars, Erzurum, Erzincan and Azerbaijani civilians in Syunik / Zangezur and Karabakh was on the hands of the fighters of the "hero of the Armenian resistance" Andranik Ozanyan alone. The massacres were violent and mutual. In case of "good work", the Greeks could count on Constantinople and the Straits, the Armenians on Sivas and Cilicia, the Kurds on compensation in Iraq for ceding part of the corridor. The Turks - nothing. And in general, the well-being of the latter would depend on how far they were prepared to "integrate" into Greek or Italian culture.

The Turks took the loss of Arab territories in their stride: within a few months they were transformed from Ottomans into proper Turks, into the Turkish nation. .... The Treaty of Sèvres, signed on 10 August 1920 by the last Sultan, Mehmet VI, had no one to ratify it. Even the Majlis Umumi (the parliament of the Ottoman Empire) rejected the imminent partition of the territory of Asia Minor (and the fate of the Arab lands and of Kars and Batum, which it proposed to decide by local referendum) and was dissolved by the Entente on 11 April. And on 23 April 1920, the first session of the GNST, consisting mainly of deputies of the Majlis, was opened in Ankara. Mustafa Kemal, who was later given the title 'Atatürk', was elected speaker of the new Turkish parliament and head of government. The next decision of the TGNA was to reaffirm the position of the Majlis.

New wars between Greece and Armenia and Turkey were now inevitable. The possibility of the Entente 'self-dismissing' was not seriously considered in these two countries. On 1 June 1920, the U.S. Senate rejected the bill to mandate the territory of Armenia, but this did not calm Yerevan. Nor did the fact that in May the Kemalists had defeated the French on the border with Syria, forcing the French to agree to an armistice. In the meantime, both Paris and London, as well as Moscow, have understood that there is no whiff of communism in Turkey. However offensive it may sound to Armenians, the neutrality of Turkey and the Straits (the future Montreux Convention of 1936) was much more important to Moscow than the ambitions of the pro-Western Republic of Armenia. As for Greece, without so much bloodshed this story could have been called an anecdote. Atatürk was so sure that the Greeks would agree to trade the Smyrna/Izmir region for Constantinople that he proposed calling the republic not "Turkish" but "Anatolian" (Anadolu Cumhuriyeti; Anatolia - Asia Minor, more widely - the whole Asian part of Turkey). The Greeks wanted both Smyrna and Constantinople.

After the Sovietisation of Azerbaijan, when the same hopes were raised for the whole of Transcaucasia, Soviet Russia made a desperate attempt to prevent an Armenian-Turkish war. On 14 September, Boris Legrand, the RSFSR ambassador in Yerevan, presented the Armenian government with proposals for settling the conflict. Since it was not in the tradition of Russian diplomacy to make promises, and since these were borrowed from the Soviets, it must be assumed that the proposals had already been agreed with Ankara. The Kemalists established contacts with Moscow as early as the spring of 1920, when one of the leaders of the All-Union Communist Party, Ahmed Mukhtar-bey, visited Moscow. A little later, he said that "during the preliminary negotiations on the establishment of friendly relations, the Russians did not set us any conditions regarding the spread of communism on the territory of our country".

The aim of the two countries was only to take measures to thwart the imperialists' plans for them. This is an answer to the "God's Horse" of Armenian historians that "Ataturk promised Lenin to build socialism and therefore Lenin betrayed Armenia". These negotiations did not take place "behind the scenes"! At the same time, the Soviets were negotiating with Armenia. In April 1920, an Armenian delegation led by Levon Nakhashbedyan arrived in Moscow. Leon Shant (his creative pseudonym) may have been a talented poet and playwright, but he had little understanding of diplomacy and talked more about the ruined monasteries of Lake Van and the medieval principality of Hamshen on the Black Sea coast. In short, Russia was already mediating.

Legrand's proposals consisted of three points: 1. Russia to act as a mediator in the settlement of Armenia's border disputes with its neighbours (the fact that Azerbaijan had already been Sovietized and Armenia was only to be appeased allowed the Armenians to hope for a favourable decision on most of the disputed territories); 2. Armenia to let the Red Army units through to the 1878, i.e. 3. Armenia refuses the Sevres Treaty (without it, the Red Army's entry into Armenia, and even more so the advance to the 1914 border, would have meant the RSFSR's acceptance of Armenia's claims to the Sevres border and preparation for war with Turkey).

It is clear that the acceptance of these proposals would also mean the Sovietisation of Armenia... That is why the Armenian government accepted the first two proposals without hesitation, but rejected the point about giving up Sevres. The peace settlement was blocked by Yerevan.

A week after "Legrand's ultimatum" (as his Armenian colleagues sometimes called him), on 20 September 1920, Armenian troops attacked Turkish "partisans" and occupied the town of Oltu (formally part of Georgia!). It is not known whether they violated the 1914 border or not, but Turkey announced an attack on its territory and launched an offensive. What followed was a crazy déjà vu based on May-June 1918. But without a new Sardarapat, Bash Aparan and Karaklis: the Turkish army, inspired by the Kemalist revolution, had a second wind.

Armenia's 8 October appeal to "all civilised mankind" went unanswered: it was the last chance for "civilised mankind" to clash with Russia and Turkey. On 18 November, an armistice was signed in Alexandropol, once again taken by the Turks. At the same time, Armenia ceded the whole of Lori and Alaverdi by agreement with Georgia, as long as the latter maintained its neutrality and kept the railway open. Aren't you tired of laughing? Then here it is: on 22 November, Woodrow Wilson offered the Allies to officially recognise Armenia's borders in accordance with the Treaty of Sèvres. Well, somehow together and loudly declare it. The Allies promised to think about it.

А! On the role of Russian arms aid to Turkey in the defeat of Armenia. The first shipment of weapons from Soviet Russia was unloaded in Trabzon on 23 September. In Trabzon, to get away from the Bosporus and the British ships. And in just one month, Turkey received 3,387 rifles. In one month, at the end of October, when the Turks were already storming Kars! And the most important thing: all the weapons for two years - rifles, machine guns, cannons, cartridges and shells - were sent to the west of Turkey, to the incomparably more important front of the Greek-Turkish war. Armenian historians should still consider the chronology and the general context of the events...

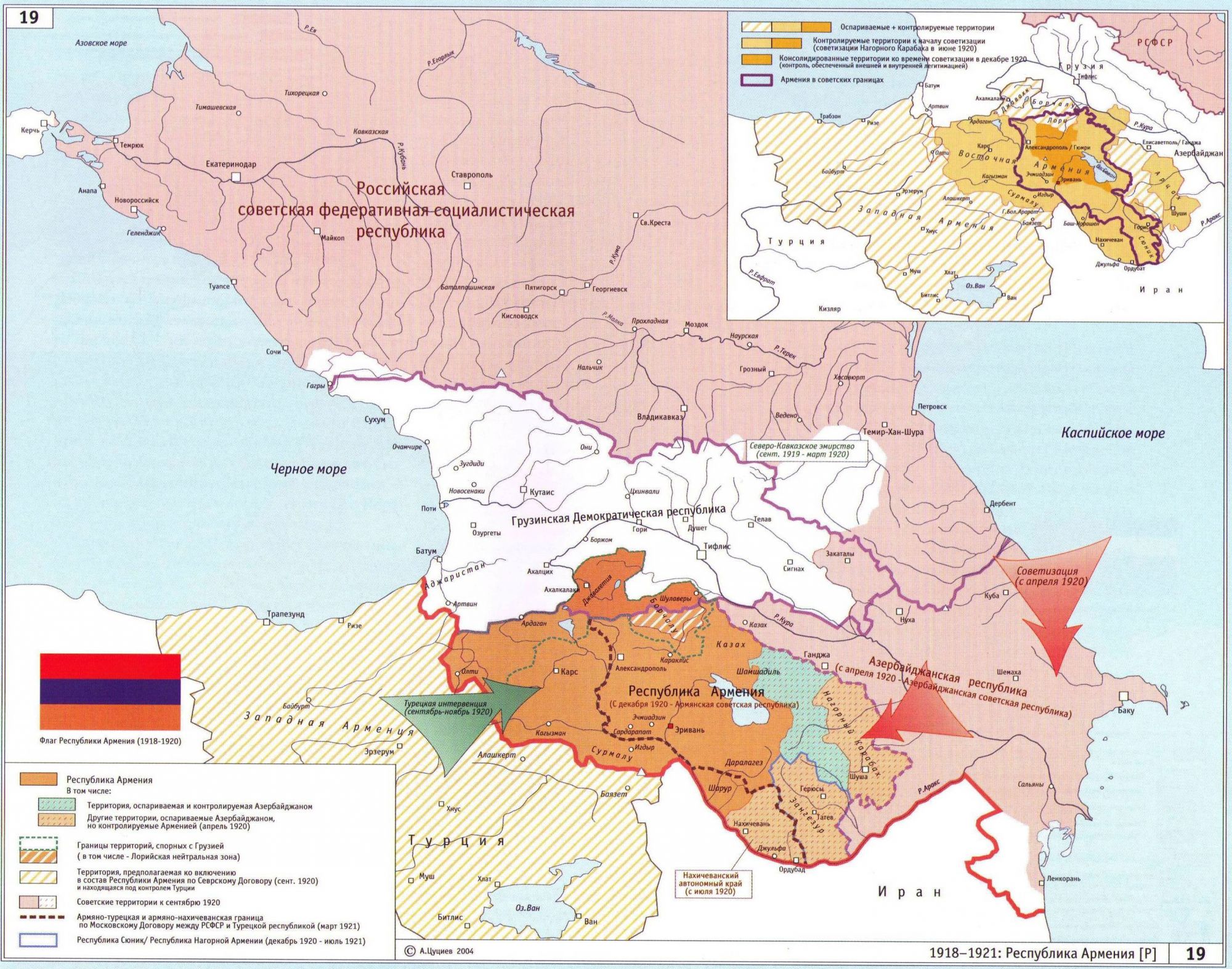

A peace treaty was signed in Alexandropol on the night of 2/3 December. A favourite theme of Armenian historians is the "legal invalidity" of this treaty. They say that by signing it, the members of the Armenian delegation "only controlled the chairs they were sitting on", because the Red Army was already entering Yerevan. Come on. Sultan Mehmet VI, who signed the Treaty of Sevres, also only controlled the chair under him. And the treaty was never ratified. Really? Who in Turkey ratified the Treaty of Sevres? The last treaty ratified by both sides was the Batumi "Treaty of Peace and Friendship" of 4 June 1918. According to this, at least Echmiadzin remained Armenian, and the yellow spot on the map looks larger than the brown spot on this map (inset in the upper right-hand corner). Moreover, this map is still spare: the entire Alexandropol-Tiflis railway zone was occupied by Turkey:

Or should the Red Army have waited a month for ratification before entering Yerevan? It is unclear, however, on what basis it would have been possible to return Echmiadzin and Alexandropol (Gyumri). The return of the border, which still exists today, was made possible by the Russian-Turkish Treaty of Moscow in 1921 and confirmed by the Treaty of Kars between Turkey and the three Transcaucasian Soviet republics in the same year. In gratitude, as he recounts in his book "Life. Cinema" about his working trip to Yerevan, director Vitaly Melnikov (The Chief of Chukotka and other remarkable films) said that every taxi driver and policeman considered it his duty to inform: "From Moscow? See that mountain? That's Mount Ararat. Lenin gave it to the Turks. Full stop.

No, they are right about one thing. The fact is that, apart from Kafia sanjak (the southern coast of Crimea), the Russian Empire had not conquered a single piece of Turkish land by 1878 (well, and Akhaltsikhe pashalik still): The Crimean Khanate, Imeretia, Mingrelia, Guria and Abkhazia were merely vassals of the Ottoman Empire. In short, in 1921, on the eve of the 1877-1878 war, Turkey insisted on the border. But Russia needed the deep-water port of Batum, and Turkey needed the poor (there were only the salt deposits of Kulpa) Surmalinskiy district between Arax and Ararat, formerly belonging to Persia: thus Ankara got a connection with Nakhchivan. So much for the exchange. The good 'news' for Armenians is that, in return, Georgia gave Armenia the Lori region with the Alaverdi copper basin, which became the basis of Armenia's industrialisation...". End of article.

As we can see, in 1920 the Hayan nationalists were asked to do nothing more than "wait" and stay away from the Turkish territories. Moreover, although Turkey lost them under the same Treaty of Sèvres (Oltu), the Entente "gave" them not to Armenia but to Georgia. And if the Treaty of Sèvres had been implemented, this would have been the case, because even physically the Oltu district would not have bordered with the territory left to Turkey, but would have been separated from it by vast areas of "Sèvres" Armenia.

Georgia did a perfectly reasonable and rational thing with Oltu. It was in no hurry to annex the Turkish lands "given" to it by the Entente. For several reasons. First of all, Georgia did not sign the Sevres treaty with Turkey. Secondly, in Oltu, unlike Adjara, the majority of the population were not Muslim Georgians but ethnic Turks. It is also possible that the authorities of democratic Georgia believed that the Treaty of Sèvres, which was unacceptable to Turkey, would sooner or later be cancelled or revised, and that the border issue would then have to be resolved through bilateral negotiations with Turkey.

But Hayan nationalists "could not wait" to get their hands on the Turkish lands. And not only that which they had been completely unreasonably "cut off" under the Treaty of Sèvres and even beyond.

Then the question arises why the Dashnaks did not go to the "almost Armenian" "Sèvres" lands of Turkey, but to Oltu, which was "foreign" to them according to the same Sèvres Treaty?

There is no doubt that the mountainous and poor district of Oltu itself was of little interest to the Hay nationalists. But they were very interested in the Georgian Adjara, to the north-west of Oltu, and the port of Batumi, to which the railway was going. The railway was never built to Trabzon, as promised in the Treaty of Sevres.

This means that the aggression of Dashnak Armenia against Turkey in 1920 was both de jure (invasion of the territory of the Oltu district without the consent of Georgia) and de facto an aggression against Georgia. And if the Turks had not resisted the Armenian aggression in Oltu, this district would have been occupied by Armenia with the subsequent movement of the Dashnaks to Artvin and Batumi.

In other words, the Georgians would have had to fight alongside Armenia for Adjara and Batumi in 1920. Just as at the end of 1918 the Georgians had to fight for Borchali and Lori with the Khai aggressors. It is important to understand this today, when Hay nationalists, including representatives of the "fifth column" in Georgia, like to scare Georgians with the alleged "Turkish threat".

Varden Tsulukidze

Read: 658

Write comment

(In their comments, readers should avoid expressing religious, racial and national discrimination, not use offensive and derogatory expressions, as well as appeals that are contrary to the law)

News feed

-

Georgian Defence Minister highlights “active” cooperation with US Defence Department

18:0026.07.24

-

Georgian PM says rehabilitation of historical Leuville Estate to conclude in 2026

17:1226.07.24

-

Culture Minister expects Georgian flag to fly, anthem played many times in Paris

16:4126.07.24

-

16:1026.07.24

-

Irakli Kobakhidze on terrorism threats: We have all the resources to oppose such plans

15:3826.07.24

-

15:0026.07.24

-

Speaker: Opposition's main goal to come into power, be puppet regime ruled by foreign forces

14:1026.07.24

-

Two missing citizens found in Svaneti

13:2726.07.24

-

13:0026.07.24

-

Georgia Global Utilities announces issuance of $300 Million Green Bonds

12:1726.07.24

-

Can Abkhazians calm down now that the law on housing in Abkhazia has been withdrawn?

11:4026.07.24

-

PM attends Sports Summit and a Reception in Paris

11:0026.07.24

-

NBG Acting President attends opening ceremony of 1st Authorised Investment Fund in Georgia

10:0526.07.24

-

18:0025.07.24

-

17:3025.07.24

-

Georgian passport advances 6 positions in int’l ranking on visa-free travel

16:4825.07.24

-

Georgian PM says “accelerating” economic growth Govt’s “most important national task”

16:0525.07.24

-

Media representatives were attacked while performing their professional duty in Tbilisi

15:3025.07.24

-

Levan Davitashvili: The construction partner of Anaklia port will be announced tomorrow

14:5025.07.24

-

NBG: National currency loans up by 785.90 million GEL, foreign currency by 180.28 million GEL

14:0525.07.24

-

13:3025.07.24

-

12:4825.07.24

-

Defense Minister: Increasing funding annually to strengthen defense capabilities

12:0325.07.24

-

11:3425.07.24

-

11:0525.07.24

-

10:2825.07.24

-

Iago Khvichia - The investigation started in SSS is based on conspiracy theories

18:0024.07.24

-

Until July 28, there will be occasional rainy weather in Georgia

17:3324.07.24

-

NDI is launching a long-term assessment mission for the 2024 parliamentary elections

17:0024.07.24

-

16:3524.07.24

-

Kakha Okriashvili about GD - Double and triple play will lead to war

16:0124.07.24

-

15:3024.07.24

-

Occupiers will 'burn' Abkhazians 'with a hot iron' for their 'Russophobia

14:5524.07.24

-

State Budget Received Record Revenue From Gasoline And Diesel Excise Tax

14:1024.07.24

-

13:0124.07.24

-

12:4124.07.24